These skills are those needed to negotiate with others, to participate in a team environment, to provide service to clients/customers/peers, and to resolve conflict. These skills are important because they aid in helping individuals and organizations accomplish their goals (Kantrowitz, 2005).

Training a New Generation of Leaders

Schatz (1997) states that traditional academics fail to respond to companies’ requirements for developing leadership practices, arguing that although training and development is supported by theories and scholars, this is not adopted by business schools.

1. Experiential learning

McCall (2004) indicates that experience is the major source of learning via training and some formal programmes. However, LD occurs also via some informal programmes, such as on-the-job mentoring and on-the-job experiences (Hartley, 2010).

2. Action learning

Marquardt (2011, p. 2) defined it as: “A powerful problem-solving tool that has the amazing capacity to simultaneously build successful leaders, teams, and organisations; it is a process that involves a small group working on real problems, taking action, and learning as individuals, as a team, and an organisation while doing so.”

“Action learning emerges the alignment between learning and action because there is no learning without action and there is in turn no action without learning” (Megheirkouni, M., 2016 and Revans.,1998).

Leonard. and Lang., (2010) Summarised action learning methods in developing leadership as follows:

- Engage the learner in the process: As Revans (1998) noted, “there can be no action with learning, and no learning without action” (p. 14). Participants who are engaged in meaningful action, with inquiry and reflection, cannot help but learn.

- Integrate new knowledge with existing knowledge: The action learning coach specifically uses this strategy when asking questions that require team members to identify not only what they learned but how these learnings can be applied in the future.

- Increase generalizability by practicing a variety of situations with increasing levels of complexity and difficulty: Early in an action learning process, the team grapples with some basic problems such as how to get organized, make decisions, and balance personal and team goals. Although these tasks and processes occur throughout the life of the team, they become more complex and complicated as the problem and goal are clarified and the solution begins to emerge.

- Increase proficiency and mastery by adding more challenges once more basic skills and knowledge are mastered: The team has multiple opportunities to practice and master the team skills necessary for high performance. As the skills are practiced, the team begins to recognize more nuances to the problem and processes.

- Use spaced practice: A key advantage of a spaced program is that it allows team members to integrate and practice new skills between sessions (Marquardt et al., 2009). In most action learning programs used for developing leadership skills, teams meet on a periodic, spaced schedule, i.e. every 2 or 3 weeks.

- Diminish external feedback: As team members become more proficient in dealing with challenges, the coach provides less feedback and encourages them to be more self-monitoring.

- Encourage mental rehearsal: Although the coach does not direct the team to rehearse for important events and meetings, they often indirectly encourage team members to mentally prepare for and rehearse before important situations (Marquardt et al., 2009).

A list of leadership competencies that can be readily developed by action learning are presented in Table 1.0

Table 1.0 Leadership Skills That Can Be Developed via Action Learning

Action Learning provides a learning environment that is particularly effective in developing the following leadership skills that lead to timely and creative solutions (Dilworth & Willis, 2003; Marquardt et al., 2009):

- When to lead and when to follow

- When to be directive and when to encourage collaboration and consensus

- How to use intrinsic as well as extrinsic motivators to keep people engaged

- How to engage people’s idealism and desire for personal development and growth to develop inspiring visions and passion

- How to empower subordinates and peers to use and develop their ability to self-manage and self-lead

- How to develop a mindset for continuous learning throughout the organization.

3. Executive coaching

An experiential and individualized leader development process that builds a leader’s capability to achieve short-and long-term organizational goals, it is conducted through one-on-one and/or group interactions, driven by data from multiple perspectives, and based on mutual trust and respect; the organisation, an executive, and the executive coach work in partnership to achieve maximum impact (The Executive Coaching Forum, 2008, p. 19).

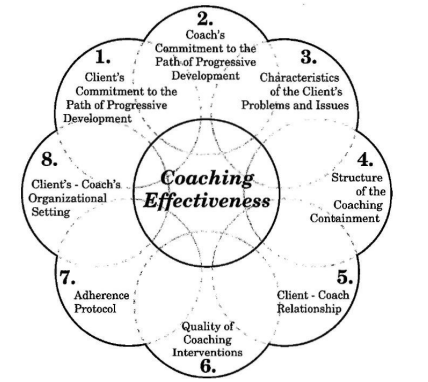

Figure 1.0 illustrates the overlapping and interpenetrating characteristics of different variables. Each of the variables contributes in major ways to whether a coaching assignment achieves its long-term goals (Kilburg and Richard R. 2001).

The model is based on the assumption that both the client and the coach have an intensive and complex commitment to the path of progressive development (Freud, 1965).

Figure 1.0: A model of coaching effectiveness.

In addition, each of these eight key elements can be thought of as consisting of a number of significant components that coaches must consider throughout the course of a coaching assignment. Some components are depicted in the Table 2.0, (Kilburg and Richard R. 2001).

Figure 2.0: Key Elements in a Model of Coaching Effectiveness

4. Networking

Lester et al (2017)presents three approaches for network-enhancing leadership development derived from prior theoretical and empirical research examining networks and leadership:

(1) Individuals Developing Social Competence

(2) Individuals Shaping Networks

(3) Collectives Co-Creating Networks.

Day & Dragoni (2015) brings attention to the importance of enhancing social networks. Broadly defined, network-enhancing leadership development consists of approaches attempting to impact individuals' and/or collectives' networked relationships in order to enhance the leadership capacity of organizations.

As Fig. 2 suggests, social and leadership networks co-evolve such that there are multi directional relationships and feedback loops between different social relationships (DeRue, 2011). Finally, and most distally, individuals' and collectives' social and leadership networks impact individuals' participation in leadership roles and processes and creation of direction, alignment, and commitment (Day & Dragoni 2015)

Collectives co-creating networks

Day and Dragoni (2015) have summarized multiple research that suggests “certain human resource policies, organizational development interventions, and workplace practices, such as communal eating (i.e., sharing meals; can promote connectivity and productivity

5. Job rotation

Short job rotations can help leaders evolve with a comprehensive understanding of the business. Companies are using various strategies to develop effective leaders. If they are not effective leaders already, companies may want to consider using job rotation assignments to build more well-rounded employees and strengthen organizations That could develop leaders in the long term (Day, D.V., 2000).

Optimising the effects of leadership development programmes

According to these reviews and meta-analyses, the common Leadership development methods that have been accepted in the literature include 360-degree feedback, executive coaching, job assignments, action learning, job rotation, networking, and mentoring. In this regard, a “one size fits all” approach to Leadership development may not be applied to all people, organisations, and countries (Weir, 2010). He claims that transferring Leadership development methods and activities to other countries requires taking into consideration several issues. For example, what strategy should be adopted; locating, and organising business units because this may require understanding the requirements for designing Leadership development programmes and understanding the elements shaping the way that people in specific contexts develop as leaders (Weir, 2010).

References:

Collins, C. J., & Clark, K. D. (2003). Strategic human resource practices, topmanagement teamsocial networks, and firmperformance: The role of human resource practices in creating organizational competitive advantage. Academy of Management Journal, 46(6), 740–751.

Cullen-Lester, K.L., Maupin, C.K. and Carter, D.R., 2017. Incorporating social networks into leadership development: A conceptual model and evaluation of research and practice. The Leadership Quarterly, 28(1), pp.130-152.

Day, D.V., 2000. Leadership development:: A review in context. The leadership quarterly, 11(4), pp.581-613.

Day, D. V., & Dragoni, L. (2015). Leadership development: An outcome-oriented review based on time and levels of analyses. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2, 133–156.

DeRue, D. S. (2011). Adaptive leadership theory: Leading and following as a complex adaptive process. Research in Organizational Behavior, 31, 125–150.

Dilworth, L. (1998), Action learning in a nutshell, Performance Improvement Quarterly, Vol. 11 No. 1, pp. 28-43.

Freud, A. (1965). Normality and pathology in childhood: Assessments of development. Writings. New York: International Universities Press.

Garcia, S. K. (2007). Developing social network propositions to explain large-group intervention theory and practice. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 9, 341–358.

Hartley, J. (2010), Public sector leadership and management development, in Gold, J., Thorpe, R. and Mumford, A. (Eds), Handbook of Leadership and Management Development, Gower, Burlington, VT, pp. 531-546.

Kantrowitz, T.M., 2005. Development and construct validation of a measure of soft skills performance. Georgia Institute of Technology.

Kilburg, R.R., 2001. Facilitating intervention adherence in executive coaching: A model and methods. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 53(4), p.251.

Kniffin, K. M.,Wansink, B., Devine, C. M., & Sobal, J. (2015). Eating together at the firehouse: How workplace commensality relates to the performance of firefighters. Human Performance, 28(4), 281–306.

Lanier, D., Jackson, F.H. and Lanier, R., 2010. JOB ROTATION AS A LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT TOOL. Consortium journal of hospitality & tourism, 14(2).

Leonard,S.H. and Lang, F., 2010. Leadership development via action learning. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 12(2), pp.225-240.

Lester,C.K.L., Maupin, C.K. and Carter, D.R., 2017. Incorporating social networks into leadership development: A conceptual model and evaluation of research and practice. The Leadership Quarterly, 28(1), pp.130-152.

Marquardt, M. (2011), Optimizing the Power of Action Learning, 2nd ed., Nicholas Brealey Publishing, London.

Marquardt, M.J., Leonard, H.S., Freedman, A.M. and Hill, C.C. (2009), Action Learning for Developing Leaders and Organizations: Principles, Strategies, and Cases, American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.

McCall, M.W. (2004), Leadership development through experience, Academy of Management Executive, Vol. 18 No. 3, pp. 127-130.

Megheirkouni, M., 2016. Leadership development methods and activities: content, purposes, and implementation. Journal of Management Development.

Porter, C. M., & Woo, S. E. (2015). Untangling the networking phenomenon a dynamic psychological perspective on how and why people network. Journal of Management, 41, 1477–1500.

Revans, R.W., 1998. Sketches in action learning. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 11(1), pp.23-27.

Schatz, M. (1997), Why we don’t teach leadership in our MBA programmes?, Journal of Management Development, Vol. 16 No. 9, pp. 677-679.

The Executive Coaching Forum (2008), Executive Coaching Handbook: Principles and Guidelines for Successful Coaching Partnership, 4th ed., Executive Coaching Forum, available at: www.executivecoachingforum.com (accessed 28 March 2022).

Weir, T. (2010), Developing leadership in global organizations, in Landy, F. and Conte, J. (Eds), Work in the 21st Century: An Introduction to Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 2nd ed., Wiley-Blackwell, San Francisco, CA, pp. 203-230.

Learning is the best way to develop the human resources of an organization. Managers and employees are increasingly taking responsibility for learning and development, rather than learning and development specialists (Armstrong 2009). Rather than providing training or instructing, the latter are becoming learning facilitators. Training is playing a smaller and smaller role. Training specialists, as Stewart and Tansley (2002) point out, are more concerned with learning processes than with the substance of training courses.

ReplyDeleteThank you so much for your insights and for your review,

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteAccording to Sommer Ville cited in Malik.S, (2018) “Training is the process that

ReplyDeleteprovides employees with the knowledge and skills required to operate within the system and standards set by management”

Yes Rifky, you are right. Thanks for the comment.

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteThank you so much, for adding this point about vital steps to be taken by those that conducts training and development Hasara.

ReplyDelete